William Lyons and William Walmsley’s Swallow Sidecars started building motorcycle sidecars in 1922, and then it soon expanded into custom bodies for affordable cars, such as the Standard 9, the Austin Seven, and later other marques. Their offerings of stylish, high-quality, low-priced bodies for inexpensive cars were naturally very successful during a depression, and in 1931, they were able to introduce a car in their own name, the SS1. Close ties with the Standard Motor Company provided Standard engines and running gear for years to come.

By 1934, Lyons and Walmsley parted ways and Lyons took full control. The 1935 SS Jaguars were SS’s first model developed fully in-house, and with Nazi Germany on the rise, they adopted the Jaguar name. Through incremental development, first of bodies and then their own chassis and suspensions for 1935, William Lyons was well on his way to his dream of a car that was completely his own.

As an enormous investment was required, engines remained the one factor outside of Jaguar’s abilities, but Standard wanted theirs custom, so they constructed not only engines but also famed engineer Harry Westlake’s new pushrod OHV heads for the Standard-based 2½-liter SS 100. These yielded 105 horsepower, which was an incredible improvement over the 68 horsepower from the side-valve straight-six in an SS90. With performance finally backing up the SS Roadster’s Le Mans body, the SS 100 2½-Litre was launched in September 1935.

As they were now selling cars in earnest (over 14,000 SS Jaguars between 1935 and 1940), Jaguar’s old-world, ash-framed construction was becoming too time consuming, and all-steel bodies were adopted for the volume-selling saloon cars for 1938. These heavier bodies required more power, so Westlake chief engineer William Heynes worked on an enlarged and improved version of the 2½-liter engine, which featured the Westlake OHV head, improved oiling and durability, twin SU carburetion, and low-restriction exhaust manifolds.

The first true performance car from SS, the SS 100 “Jaguar,” breathed new life into the gorgeous design of its predecessor, the SS 90, as it had a revised radiator, new headlamps, and a sporty Le Mans-type fuel tank. Under the hood was markedly improved performance, as it featured a new 102-horsepower, overhead-valve, six-cylinder engine with a new cylinder head and dual SU carburetors. The model was named for the top speed that it could reach, 100 mph, and it quickly became popular with enthusiasts. That enthusiasm has never waned.

SS 100 marketing literature described it as having been “designed primarily for competition work, (but) equally suitable for ordinary road use, for despite the virility of its performance, it is sufficiently tractable for use as a fast touring car without modification.” Many owners took this to heart and used their cars both as primary transportation and in many forms of motorsport, including on hill climbs, rallies, and road races. As a result, an SS 100 was a common sight at such circuits as Donington Park and on RAC rallies.

Again the engine was sourced from Standard but had the cylinder head reworked by SS to give 105 bhp. Unlike the 1½ Litre there were some drophead models made post-war.

The chassis was originally of 119 in (3,020 mm) but grew by an inch (25 mm) in 1938 to 120 in (3,050 mm). The extra length over the 1½ Litre was used for the six-cylinder engine and the passenger accommodation was the same size.

The name Vanden Plas is most frequently seen in conjunction with Bentleys and, yes, Jaguars, but the Jaguar offered here is a “Vanden Plas” of another country. It was bodied not by the famous British coachbuilder but by its Belgian ancestor, Carrosserie Van den Plas of Antwerp, originally established in 1870 to build carriage axles and wheels. Eventually, the firm had progressed to the building of entire carriages and, by the 1930s, was reigning supreme as Belgium’s foremost builder of custom automobile bodies that, in the words of The Times of London, “had an air of distinction lacking in many of the products around them.”

Yet, World War II had its effect on the firm, as it did with all other European coachbuilders. Van den Plas would survive through its own strong will and lived long enough after the war to build several further interesting bodies, with the fuller-figured curves and broad chrome embellishments that were coming into style. Evidence from these designs shows that Van den Plas looked for inspiration in this period to France, particularly the “teardrop” creations of Figoni et Falaschi, which had set the styling world on its ear in the late 1930s.

According to history that has long accompanied this car, SS 100 Jaguar chassis number 49064, the last 2½-Litre chassis built in 1939 per the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust, was purchased by Van den Plas as a basis for a custom body prior to World War II. The war prevented the project from continuing, and the chassis managed to survive the conflict. Thus, when it came time for Van den Plas to return to coachbuilding, they looked to the only chassis they had readily on hand as the basis for their first show car, an all-important creation that would hopefully attract new business during the lean immediate post-war period.

However, post-war plans were that Jaguar would assemble automobiles in Belgium using part of the Van den Plas works, indicative of an increasing partnership between the two firms. This was one of two Van den Plas–bodied Jaguars displayed at the 1948 Brussels Motor Show, the other of which was even used on the back of the Belgian Jaguar distributor’s brochure for the Mark IV in 1948. Rather than chosen because it was the only chassis available, the SS 100 was likely a conscious choice, designed by the coachbuilder to show the British automaker what amazing (and highly profitable) things could come from a Jaguar and Van den Plas partnership.

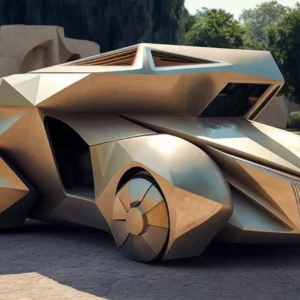

The completed creation nonetheless shows the juxtaposition of post-war expediency and lavish pre-war Figoni-inspired design. Sweeping fenders follow the original basic lines of the factory SS 100’s lavish curves but are fully and deeply skirted, wrapping down to the chassis frame. Broad sweeps of chrome trim reach from the front bumper up around the arches of the wheels, drip seductively down into the fenders, and then extend back to a flared droplet-shaped embellishment on the rear-wheel spat. Further delicate bright metal trim surrounds the steeply raked windshield and the upper beltline of the body; indeed, the stunning effect of the brightwork is derived from its judicious application throughout the car rather than being focused on a few moldings.

Yet, close examination shows that both the SS’s original headlamps and radiator shell remain intact. They have simply been blended into the lines of the body so successfully that they look as if they were always meant to be there.

As previously mentioned, Van den Plas displayed their completed creation, with considerable pride, it can be imagined, at the Brussels Motor Show of 1948, an appearance which merited mention in the February 20, 1948, issue of Autocar (p. 167) and the February 18, 1948, issue of The Motor (p. 66). The latter writer described the car as being “a really remarkable example of fine lines and good proportion. The aluminum facia [sic] panel was engine-turned in traditional style.” An interesting comment in the same Motor article reiterates the news of the planned Jaguar and Van den Plas partnership that the car was intended to signal.