The late Seventies were not a time which Lamborghini looks back on with any great affection; the 1973 oil crisis and resulting recession had drained the manufacturer’s finances, while Ferruccio Lamborghini had relinquished his controlling stake in the company to see out his final years on a lakeside estate in Perugia.

To stem the haemorrhaging of its finances, the new owners began taking on contracts from external companies. One came from BMW, which entrusted Lamborghini with the development of the chassis of the M1 supercar (unlike the Italians, BMW had no experience of building mid-engined supercars) and manufacture of the 400 units required for homologation. Another was to build an all-terrain vehicle for the U.S. military on behalf of Mobility Technology International, this being accepted with the view to winning a lucrative contract and easing the financial strain at Sant’Agata. On the back of these promising opportunities, the management borrowed a substantial sum from the Italian government.

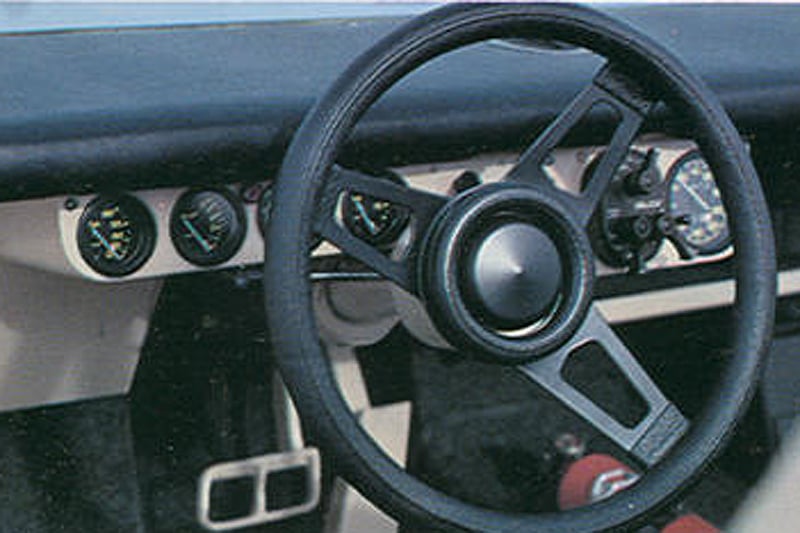

Working from plans sent by MTI from the States, Lamborghini set about building a prototype to undergo military testing – however, unbeknownst to the Italians, MTI had ‘borrowed’ the majority of the design from an earlier candidate: the FMC XR311. When the glassfibre body arrived in Italy, a waterproofed 5.9-litre Chrysler V8 was installed, connected to a 3-speed automatic transmission and mounted at the rear. Not only did its position give the Cheetah erratic handling due to undesirable weight distribution, but the engine provided the 2-tonne vehicle with a meagre 180bhp. Nevertheless, the Cheetah made its debut at the 1977 Geneva Motor Show to preview a planned civilian version, in turn triggering legal action against MTI and Lamborghini from FMC.

The Cheetah project had absorbed much of the funds intended for developing and manufacturing the M1, and after witnessing one farcical management decision after another, BMW pulled the contract from Lamborghini’s grasp. Subsequently, the one-off Cheetah was crashed and destroyed during military testing, and the company that sired it looked to be heading towards a similar fate. In August 1978, Lamborghini plunged into receivership, all but ending the Cheetah’s chances for production. Coincidentally, the military contract was won by the ill-fated Humvee.

With new investment came new opportunity. When its new owners reviewed the company in the early Eighties, they decided that the idea behind the Cheetah wasn’t scatter-brained – only its execution was. Work commenced on a successor, which was christened LM001 (‘Lamborghini Militaria no.1’) and was previewed at the 1981 Geneva Show, with just enough changes to avoid resurrecting conflict with FMC. A follow-up prototype arrived the year after, this time placing the engine at the front of the vehicle and thus solving the issue of poor handling under acceleration. LMA002 (‘A’ standing for ‘anteriore’, meaning ‘front’ in Italian) also supplanted the lazy American V8 with the 370bhp 4.8-litre V12 from the Countach LP500S, which had morphed into 5.2-litre 450bhp Quattrovalvole form by the inauguration of the production LM002 in 1986.

The LM002 went on to shape its own story, as will the Urus when it inevitably reaches production. Nowadays, the company is thankfully in much better hands than it was during the late Eighties, and while the idea of the Urus may irritate purists, it certainly appears to be destined for commercial success. It seems ironic that the Cheetah and its LM002 successor have effectively provided the company with the historical licence to justify production of the SUV, and hence might ensure its long-term financial prosperity. For that, we should all be grateful.