BUDAPEST — Jozsef had something of an epiphany while watching the Hollywood blockbuster Gladiator around two decades ago in Hungary.

He marveled at the garb, the weapons, and other accoutrements of the Roman warriors depicted in the Ridley Scott film and wondered how he could acquire such artifacts himself.

“I wasn’t interested in the history behind the objects, but in owning them, having them in my own display case, and because of that I began like crazy to research where I could find them,” Jozsef, who requested his real name not be used, recently recounted to RFE/RL’s Hungarian Service.

Jozsef soon realized that such artifacts could be had, but only those buried under the ground for centuries. He joined up with a friend, bought a metal detector, and began prospecting for treasure.

“I bought a metal detector and it wasn’t long before I was finding things. But I wasn’t really too happy because I was only interested in the Roman era, nothing else,” he explained.

Centuries ago, the frontiers of the Roman Empire cut across today’s Hungary with the Danube River effectively serving as a dividing line. To the east, the archeological sites and treasures to be found mostly originated with the Avars, the Huns, and the Hungarian royals from the House of Arpad, who reigned from 1000 to 1301.

To the west, the ancient objects in the ground are often of Roman origin. These are the treasures that are valued more on the market and much of it is traded illegally.

In the communist era, treasure hunters equipped with metal detectors were a rarity in Hungary, although the activity did gain some traction in the 1980s. Nevertheless, as a result, there is still much untouched archeological treasure to be had in Hungary, experts say, although it is vanishing fast.

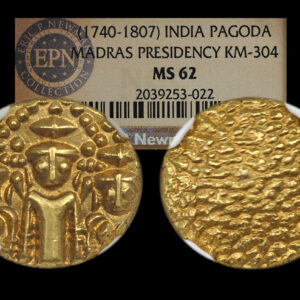

Treasure hunters are digging up coins, statues, and gold objects, taking everything that can be moved, experts warn. The more valuable pieces are either sold in Budapest or taken to Vienna, largely recognized as the center of the Eastern European and Balkan illegal art and antiquities market. Small-time treasure hunters hawk their wares online in Hungary.

Almost a decade ago, you could even buy a Roman-era sarcophagus online. Anyone can buy a metal detector in Hungary, but the law practically prohibits its use — but almost no one obeys the law, and the authorities have bigger worries than hunting down illegal metal detectors.

Archaeologists are not happy. They have now found themselves competing with treasure hunters, but fear they probably lost the battle long ago. Experts call for stronger laws, but acknowledge that tougher legislation likely won’t eliminate the illegal trade in the country’s heritage.

“Over the past two decades, legislation has tried to address this metal-detector activity, but a new approach is definitely needed. The Heritage Protection Act is now into its 66th version, but is barely 21 years old and its regulations cover in different ways what and how instruments can be used at an archaeological site,” said Gabor Viragos, deputy director general of Hungary’s National Archaeological Institute, in comments to RFE/RL.

According to Jozsef, who now lives in a village near Szekesfehervar, a city in central Hungary, people equipped with metal detectors can be found everywhere.

“In every village, there is someone who has a metal detector. There are probably at least 2,300 active treasure hunters in this country, although the number is probably much higher than that. Very often, the local commissioner himself [is one of them], since he is the only police officer in the area, is not checked by anyone at all, since he is the local chief there, who monitors everyone else, but can rob as he pleases.”

Jozsef moved to the area years ago, knowing it was awash with antiquities buried under the ground. After scoping out all the local archeological sites, he gave up his old life — details of which he declined to divulge — deciding instead to live off the gains from trading antiquities on the black market.

Also handy for him was an 11-tome series on the archeological topography of Hungary, with the fifth, seventh, and ninth parts especially enlightening, mapping out choice archeological sites in the Pest and Komarom counties, which were especially rich in Roman ruins and relics.

However, since hundreds of others had consulted the same books, those mapped-out areas turned out to be largely tapped out of treasure, Jozsef said.

Lacking the proper paperwork and permits, Jozsef said he and his partner acted in stealth.

“Wherever we went, we scouted the terrain well beforehand using satellite images and maps, and we always tried to work in such a way as not to be seen. If a car came by, we watched from a distance, [and] we always told each other on walkie-talkies if we saw any suspicious movement while we were digging. We always hid our car so that if there was trouble and we had to run, we could reach it before they caught us. We left the car in the village and walked out into the field or the forest,” he explained.

Although they rarely returned empty handed, Jozsef said the loot they found was rarely lucrative.

“I didn’t find as much as I thought I would, and it started to not be worth it in terms of time and money. My hands hurt, I was muddy, and in half a day I regularly found nothing more than four small bronze coins,” he complained.

“But I wanted to find much better ones, and more beautiful ones, and I really liked fibulae (Roman brooches or pins), the ones that are special, the ones shaped like an animal, or the enameled ones. Well, these are the ones I wanted to find, clean them, and put them in the display case.”

After six years of treasure hunting, Jozsef packed it in, selling off his equipment worth thousands of dollars and began an even more profitable business as a broker of ancient coins.

“I bought 1,000 or 2,000 coins a week…. In five or six years, I earned $500,000-$700,000 on Roman coins alone,” Jozsef said, adding that he ultimately traded the Roman coins for modern Hungarian ones, earning not only extra profit but easing his ability to “withdraw this money legally.”

Tougher Measures, Largely Unenforced

Those maneuvers, he said, were largely dictated by the tightening of EU legislation in 2018 to combat money laundering and terrorist financing, confounding illegal art dealers, especially those operating on eBay, the online auction website. As a result of the changes, in Hungary, for example, any transaction between PayPal and a bank account of over 2 million forints ($4,680) could mean the tax authorities were notified.

Despite the tougher oversight, Viragos explained, illegal treasure hunters have nothing to fear even though the laws on the books — even on owning a metal detector — are stringent. “Even though the regulations are relatively strict, nobody can or wants to enforce them effectively at the moment,” said Viragos.

According to the law on the protection of cultural heritage sites, everything buried in the ground in Hungary is the property of the state. Moreover, although anyone can buy a metal detector in Hungary, a 2015 law effectively banned their use. That’s because a private individual must obtain a permit to use a metal detector outside of an archaeological site, which are, naturally, out of bounds. However, the process is so convoluted that almost no one is ever granted one, encouraging many to forego the process.

Archeological Sites Being Stripped

There are more than 100,000 protected archaeological sites in Hungary, which have been systematically looted since the 1980s — and not only by Hungarians, experts say.

“Artifacts have disappeared from the top layer of the earth. Larger objects and coins were stolen first. Metal detectors are now more and more sophisticated, they can see deeper and deeper into the ground. The disappearance of artifacts has accelerated…. And there is not much left in the fields 40 or 50 centimeters deep. They are practically empty,” said Istvan Vida, the head of the coin department of the Hungarian National Museum.

“If it continues like this, in 10 to 15 years the top 20 to 30 centimeters of the soil will be vacuumed up in Hungary. New finds will only appear if they plow down to a depth of 80 centimeters. The damage is incalculable,” added Viragos. “There are still illegal excavations today. In the past, all the finds from an Arpad-era cemetery were excavated and stolen. But the Roman villas are also looted to this day.”